Mastering the Deep Research Process: Step-by-Step Guide [2025]

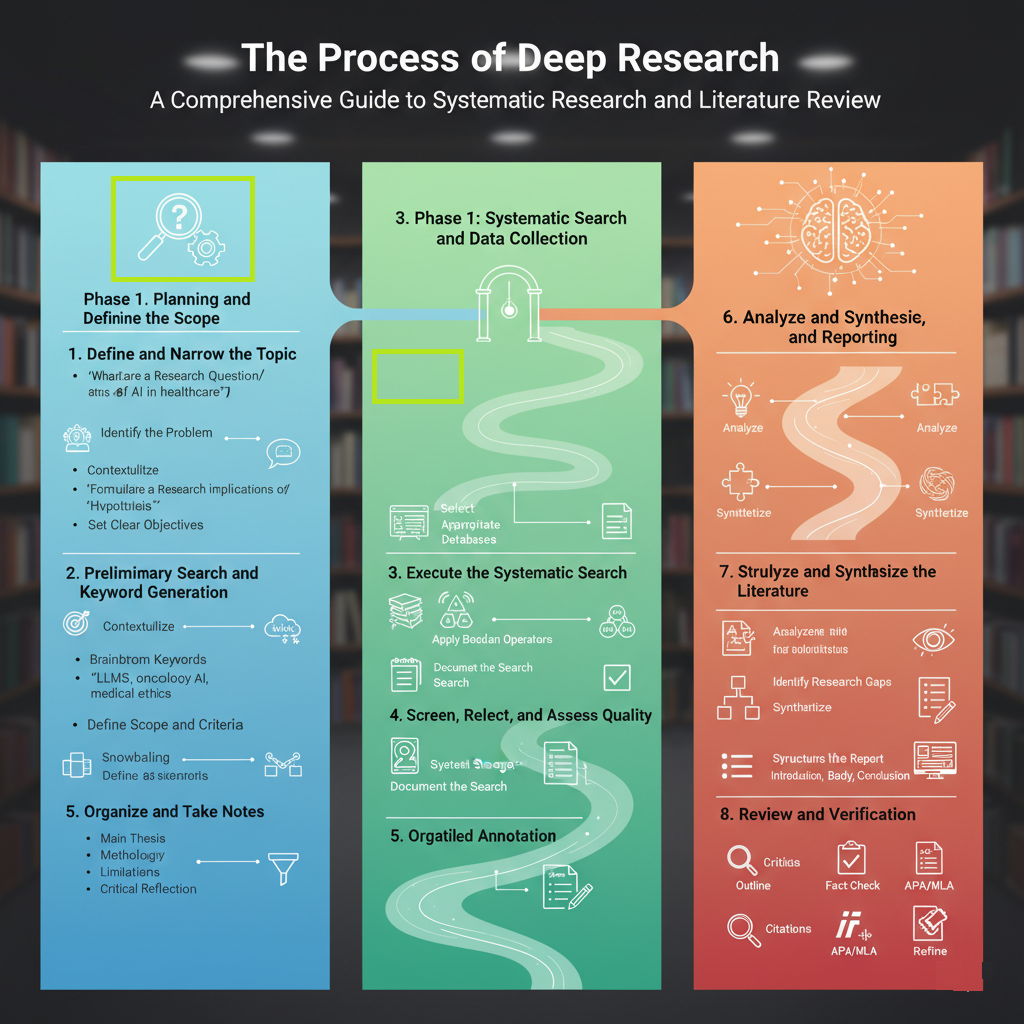

The process of conducting deep research, often referred to as systematic research or a Comprehensive Literature Review (CLR), involves a structured, multi-step methodology to go beyond surface-level information and achieve a profound, synthesized understanding of a topic.

Deep research process focuses on critically evaluating a large volume of high-quality sources, identifying patterns, uncovering gaps in current knowledge, and generating new insights.

Here is a comprehensive, step-by-step guide on how to conduct a deep research study:

Phase 1: Planning and Defining the Scope

This phase establishes the foundation, scope, and objectives of the research.

1. Define and Narrow the Topic:

- Identify the Problem: Start with a broad area of interest (e.g., “AI in healthcare”).

- Formulate a Research Question/Hypothesis: Refine the topic into a specific, answerable question (e.g., “What are the ethical implications of using Large Language Models for diagnostic support in oncology, and what regulatory frameworks exist to address them?”). A specific question ensures focus and feasibility.

- Set Clear Objectives: Establish what the research aims to achieve (e.g., “Identify the top three ethical dilemmas,” “Compare US and EU regulatory approaches,” “Synthesize a set of best-practice recommendations”).

2. Preliminary Search and Keyword Generation:

- Contextualize: Conduct a brief preliminary search using general resources (e.g., encyclopedias, initial academic searches) to understand the landscape, key players, and core concepts.

- Brainstorm Keywords: Develop a comprehensive list of keywords, synonyms, and related technical jargon (e.g., ‘LLMs,’ ‘oncology AI,’ ‘clinical decision support systems,’ ‘medical ethics,’ ‘EU AI Act’). This is crucial for the next step.

- Define Scope and Criteria: Determine the inclusion/exclusion criteria for sources (e.g., only peer-reviewed journals, articles published within the last 5 years, specific geographic regions).

Phase 2: Systematic Search and Data Collection

This phase is about rigorously and transparently gathering the necessary literature and data.

3. Execute the Systematic Search:

- Select Appropriate Databases: Use academic, professional, and specialized databases relevant to the topic (e.g., Google Scholar, PubMed, arXiv, governmental/regulatory websites for legal topics).

- Apply Boolean Operators: Use operators like AND, OR, and NOT to combine keywords effectively, ensuring the search is comprehensive yet targeted (e.g., (“LLM” OR “Large Language Model”) AND “oncology” NOT “radiology”).

- Document the Search: Keep a meticulous record of all databases searched, the exact keywords and search strings used, and the dates of the search. This is essential for transparency and replicability.

- Snowballing: Examine the reference lists of high-quality, relevant articles (especially survey papers or existing literature reviews) to find other seminal or critical works that may have been missed.

4. Screen, Select, and Assess Quality:

- Screening: Review the titles and abstracts of the search results against your inclusion/exclusion criteria to filter out irrelevant material.

- Full-Text Review and Selection: Read the full text of the remaining articles. Only select those that directly contribute to answering your research question.

- Quality Assessment (Critical Evaluation): Do not simply accept every source. Evaluate the credibility, authority, accuracy, and purpose of each source (e.g., using the CRAAP Test or similar assessment frameworks). Look for methodological flaws, bias, or unsupported claims.

5. Organize and Take Notes:

- Systematic Storage: Use reference management software (like Zotero, Mendeley) to store and organize the full citation information for every source.

- Detailed Annotation: For each selected source, create structured notes that capture:

- The Main Thesis/Argument.

- The Methodology used (e.g., quantitative survey, qualitative case study).

- The Key Findings/Data.

- The Limitations of the study.

- Your Critical Reflection on the source’s contribution to your research question.

Phase 3: Analysis, Synthesis, and Reporting

This is the most crucial phase where the raw data is transformed into coherent knowledge.

6. Analyze and Synthesize the Literature

- Analyze: Group the sources based on their main arguments, methodologies, or findings (e.g., thematic analysis). Compare and contrast the different perspectives. Identify common trends, areas of consensus, and, critically, areas of disagreement or contradiction in the literature.

- Identify Research Gaps: Look for unanswered questions or areas that have not been adequately addressed by existing research. The gap is often where your research makes its unique contribution.

- Synthesize: Move beyond merely summarizing individual sources. Synthesis involves weaving the information from different sources together to build a new, cohesive argument that answers your research question. Show how different sources “talk” to each other, highlighting connections and relationships.

- 7. Structure and Draft the Report

- Outline: Create a logical structure for your final report or paper. Common organizational structures for a literature-based report include:

- Chronological: Tracing the development of the topic over time.

- Thematic: Grouping the review by recurring central concepts.

- Methodological: Comparing studies based on the research methods they employed

- Drafting: Write the report with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Introduction: Introduce the problem, state your specific research question, and outline the scope and structure of the review.

- Body: Dedicate sections to the different themes, trends, and debates identified during the synthesis phase, ensuring the discussion is evidence-based and critical.

- Conclusion: Summarize the major findings, re-emphasize their significance, point out the remaining research gaps, and suggest directions for future study.

8. Review and Verification:

- Critical Review: Review the draft to ensure the arguments are logical, the flow is smooth, and the evidence is accurately represented.

- Fact-Check: Verify all critical claims and data points against the original sources.

- Citations: Ensure every piece of information and every argument drawn from an external source is correctly cited using a consistent style (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago)

- Refine: Iterate and refine the report until it meets the standard of being comprehensive, critical, and well-supported.

AI Tools for Deep Research in 2026

How to Use AI for Deep Research in 2026

The landscape of deep research has been revolutionized by artificial intelligence. What once took researchers weeks can now be accomplished in days—but only if you use the right tools and approaches. Here’s your complete guide to AI-powered research in 2026. Once you’ve mastered AI agents for research, explore our guide on AI Agents for Business Automation…”

ChatGPT Deep Research Mode: Your AI Research Assistant

OpenAI’s Deep Research mode represents a significant breakthrough for researchers conducting comprehensive literature reviews. Unlike standard ChatGPT interactions, Deep Research mode operates autonomously over extended periods, conducting multi-step research workflows without constant human intervention.

How It Works: Deep Research mode accepts your research question, develops a research plan, searches the web systematically, synthesizes findings across multiple sources, and delivers a comprehensive report with citations. The entire process can take 5-15 minutes depending on complexity, during which the AI autonomously follows research threads and refines its approach based on what it discovers.

Best Use Cases:

- Initial literature scans for new research topics

- Market research and competitive analysis

- Technical background research

- Identifying key papers and thought leaders in a field

- Generating research outlines and frameworks

How to Use It Effectively: Start with a focused research question rather than broad topics. Instead of “research climate change,” try “analyze the economic impact of carbon pricing policies in EU countries 2020-2025.” Be specific about the depth and format you need. Request structured outputs like “provide findings organized by theme with supporting evidence” rather than accepting generic summaries.

Limitations to Know: Deep Research excels at breadth but may miss nuance in highly specialized academic fields. Always verify citations—the AI sometimes generates plausible-sounding but incorrect references. Use it as a starting point and supplement for your research, not a replacement for critical analysis.

Pro Tip: After receiving your Deep Research report, ask follow-up questions to explore specific findings in more depth. The AI maintains context and can elaborate on any section of its research.

Claude Projects: Organizing Your Research Like Never Before

Anthropic’s Claude Projects feature transforms how researchers manage long-term research initiatives. Unlike single conversation threads, Projects maintain persistent context, custom instructions, and uploaded documents across multiple sessions.

Setting Up a Research Project: Create a dedicated Project for each major research initiative. Upload your key papers, data files, and reference materials—Claude can process PDFs, spreadsheets, and text files up to several hundred pages. Add custom instructions defining your research methodology, citation style, and analysis framework.

Powerful Research Workflows: Use Claude Projects to maintain a living literature review. As you read papers, upload them to your Project and ask Claude to extract key findings, methodologies, and citations. The AI builds an evolving understanding of your research domain. For systematic reviews, upload your inclusion/exclusion criteria and have Claude help screen abstracts and full texts for relevance.

Knowledge Synthesis: Claude excels at synthesizing information across multiple documents. Ask questions like “compare the methodologies used in these five papers” or “identify common themes across this literature.” The AI can identify patterns, contradictions, and gaps in the research that might take humans hours to spot.

Research Writing Support: Draft literature review sections by asking Claude to synthesize findings from your uploaded papers on specific themes. The AI maintains academic tone and can adapt to different citation styles. Always verify claims against source documents, but Claude dramatically accelerates the writing process.

Collaborative Features: Share Projects with research team members for collaborative analysis. Multiple researchers can interact with the same knowledge base, ensuring consistent understanding and interpretation of sources.

Best Practices: Organize files logically within Projects using descriptive names. Regularly update your custom instructions as your research evolves. Create separate Projects for distinct research questions to avoid context confusion.

Perplexity AI: Academic Search Reimagined

Perplexity AI has emerged as the premier AI-powered search tool for academic research, combining real-time web access with LLM reasoning to deliver cited, verifiable information.

What Makes Perplexity Different: Unlike ChatGPT or Claude, Perplexity searches the internet in real-time and provides inline citations for every claim. This transparency makes it invaluable for academic research where source verification is critical. The Pro version offers access to academic databases and advanced search modes.

Academic Search Mode: Perplexity’s Academic mode specifically targets peer-reviewed papers, preprints, and scholarly sources. It automatically prioritizes results from journals, conference proceedings, and academic institutions over general web content.

Research Workflows: Use Perplexity for exploratory research on unfamiliar topics. Ask questions like “what are the leading theories explaining X phenomenon” and receive an overview with citations to key papers. For literature discovery, query “recent papers on [topic] published after 2023” to find cutting-edge research.

Citation Mining: One of Perplexity’s most powerful features is citation chaining. When it references a paper, ask follow-up questions about that specific source. “Tell me more about the methodology in [cited paper]” or “what papers have cited this work?” to explore research networks.

Comparison with Traditional Databases: While Google Scholar and PubMed remain essential for comprehensive searches, Perplexity excels at understanding natural language questions and synthesizing information across sources. Use it for initial exploration and context-building, then verify with traditional academic databases.

Advanced Techniques: Combine search operators with natural language. “site:arxiv.org latest papers on transformer architectures” leverages both Perplexity’s AI understanding and targeted search constraints.

Limitations: Perplexity’s academic coverage depends on publicly available content. Papers behind paywalls may be referenced but not fully analyzed. Some highly specialized databases may not be fully indexed.

Specialized Research AI Tools

Beyond the major platforms, specialized AI tools address specific research needs:

Consensus: An AI-powered search engine exclusively for peer-reviewed research papers. Consensus analyzes findings across hundreds of papers to answer specific research questions with evidence-based summaries. Particularly valuable for evidence synthesis and systematic reviews.

Elicit: Designed for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, Elicit automates paper screening, data extraction, and evidence synthesis. Upload your research question and inclusion criteria; Elicit identifies relevant papers and extracts key data points into structured tables.

SciSpace (formerly TypeSet): Combines AI explanations of complex papers with literature search and citation management. Particularly useful when reading papers outside your primary expertise—SciSpace can explain technical concepts, mathematical notation, and domain-specific terminology.

ResearchRabbit: AI-powered literature discovery that maps research networks visually. Start with a seed paper and ResearchRabbit identifies related work through citation analysis and semantic similarity. The visual interface helps identify research clusters and key papers.

Scholarcy: Automatically generates structured summaries of research papers, extracting key information like methodology, results, and limitations. Valuable for rapid literature screening and building annotated bibliographies.

Semantic Scholar: Allen Institute’s AI-enhanced academic search engine that uses machine learning to understand paper content and connections. Particularly strong for computer science and biomedical research.

Integrating AI Tools into Your Research Workflow

The key to effective AI-assisted research is combining tools strategically rather than relying on any single platform:

Phase 1 – Exploratory Research: Use Perplexity or ChatGPT Deep Research for initial topic exploration and question refinement. Get broad understanding and identify key concepts and terminology.

Phase 2 – Literature Discovery: Deploy Consensus, ResearchRabbit, or Semantic Scholar for systematic paper discovery. Build your core literature set using traditional databases (Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Science) combined with AI recommendation engines.

Phase 3 – Literature Organization: Create a Claude Project or use Elicit to organize and analyze your collected papers. Upload papers and extract key information systematically.

Phase 4 – Synthesis and Analysis: Use Claude or ChatGPT to synthesize findings across papers, identify themes, and highlight gaps or contradictions. Have AI draft synthesis sections while you maintain critical oversight.

Phase 5 – Writing and Citation: Leverage AI writing assistants for drafting while ensuring all claims are verified against source materials. Use tools like SciSpace for proper citation formatting.

Critical Principle: AI tools amplify researcher capabilities but don’t replace researcher judgment. Always verify AI-generated claims against source materials, maintain critical analysis, and recognize AI limitations in your specific domain.

Best Practices for AI-Enhanced Research

Verify Everything: AI tools occasionally generate plausible-sounding but incorrect information. Cross-check key facts and citations against source documents.

Maintain Research Ethics: Ensure AI usage complies with your institution’s academic integrity policies. Properly attribute AI assistance where required. Never present AI-generated content as your original analysis without verification.

Combine AI with Traditional Methods: Use AI tools to accelerate and enhance traditional research methods, not replace them. Systematic database searches, manual paper screening, and expert consultation remain valuable.

Document Your Process: Keep records of which AI tools you used, what queries you ran, and how you verified results. This supports research transparency and reproducibility.

Stay Current: AI research tools evolve rapidly. What’s cutting-edge today may be obsolete in months. Regularly explore new tools and features as they emerge.

The integration of AI into deep research represents not just a technological shift but a methodological evolution. Researchers who master these tools while maintaining rigorous standards will conduct more comprehensive, efficient research than ever before.

You may also check our article AI Research Agents: Complete Implementation Guide 2026.

Frequently Asked Questions About Deep Research

Q: What is the difference between deep research and regular research?A: Deep research (also called systematic research or Comprehensive Literature Review) follows a structured, multi-step methodology to examine a topic exhaustively, while regular research may be more surface-level or ad-hoc. Deep research involves defining clear research questions, conducting systematic literature searches across multiple databases, using explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria, critically appraising sources for quality and bias, synthesizing findings thematically, and documenting the entire process for reproducibility. Regular research might involve quick Google searches or reading a handful of papers without systematic methodology. Deep research is essential for academic dissertations, evidence-based policy making, systematic reviews, and any situation requiring comprehensive understanding of a topic.

Q: How long does a comprehensive literature review typically take?A: A thorough Comprehensive Literature Review (CLR) typically requires 4-12 weeks depending on scope, topic complexity, literature volume, and researcher experience. Breaking this down: 1-2 weeks for research question refinement and search strategy development, 2-4 weeks for systematic searching across databases and screening results, 2-3 weeks for full-text reading and quality assessment, 1-2 weeks for synthesis and analysis, and 1-2 weeks for writing and documentation. Highly specialized topics with limited literature may take less time, while broad interdisciplinary topics could require several months. Using AI tools like ChatGPT Deep Research, Claude Projects, or Perplexity can reduce timelines by 30-50% while maintaining rigor, particularly in the initial search and synthesis phases.

Q: What are the best databases for systematic research in 2026?A: The optimal databases depend on your research domain, but key resources in 2026 include Google Scholar (broadest coverage across disciplines, free access, useful for initial scoping), PubMed/MEDLINE (life sciences, medicine, health), Web of Science (multidisciplinary, strong citation tracking), Scopus (similar to Web of Science, slightly broader coverage), IEEE Xplore (engineering, computer science, technology), JSTOR (humanities, social sciences), PsycINFO (psychology, behavioral sciences), ERIC (education research), and arXiv (physics, mathematics, computer science preprints). For business research, add Business Source Complete and Emerald Insight. New in 2026: Semantic Scholar and Consensus offer AI-enhanced search with improved result relevance. Best practice is to search 3-5 databases to ensure comprehensive coverage while avoiding excessive duplication.

Q: Can AI tools replace human researchers in conducting literature reviews?A: No, AI tools augment but do not replace human researchers in conducting rigorous literature reviews. While AI excels at rapid information gathering, initial paper screening, identifying themes across large bodies of literature, generating summaries and synthesis drafts, and suggesting connections between papers, humans remain essential for critical evaluation of methodology and bias, nuanced interpretation requiring domain expertise, recognizing subtle contradictions or gaps, making judgment calls on inclusion/exclusion edge cases, and ensuring ethical research practices and academic integrity. The optimal approach in 2026 combines AI efficiency with human expertise: use tools like ChatGPT Deep Research for initial exploration, Claude Projects for organization and synthesis, and specialized tools like Elicit for data extraction, while researchers provide strategic direction, quality control, and critical analysis. Think of AI as a highly capable research assistant that accelerates your work but still requires your supervision and judgment.

Q: What is the PRISMA framework and should I use it?A: PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) is a standardized framework for conducting and reporting systematic reviews, particularly in health sciences. It provides a 27-item checklist covering all phases of a systematic review from protocol development through final reporting, plus a flow diagram visualizing the literature screening process. You should use PRISMA if you’re conducting a formal systematic review for publication, working in health sciences or medicine where PRISMA is often required, seeking to maximize transparency and reproducibility, or planning a meta-analysis combining quantitative data across studies. PRISMA may be excessive for exploratory literature reviews, preliminary research scoping, non-academic business research, or rapid evidence assessments with tight time constraints. Many journals require PRISMA compliance for systematic reviews, so check your target publication’s guidelines. In 2026, tools like Covidence and Elicit automate much of the PRISMA workflow, making compliance easier than ever.

Q: How do I avoid bias in my literature review?A: Avoiding bias in literature reviews requires systematic procedures and conscious effort across all research phases. Develop a detailed protocol before starting that specifies inclusion/exclusion criteria, search strategy, and analysis methods—this prevents post-hoc rationalization. Use multiple databases to avoid single-source bias and reduce dependence on any one search algorithm. Define inclusion/exclusion criteria objectively before screening papers to prevent selecting only literature supporting your hypothesis. Have two independent reviewers screen papers and resolve disagreements through discussion or a third reviewer—this dramatically reduces selection bias. Actively search for contradictory evidence and papers that challenge your assumptions rather than just confirming views. Document all decisions about including/excluding papers with explicit rationale. Assess publication bias—consider that positive findings are more likely to be published than null results. Use critical appraisal tools to evaluate study quality systematically. Be transparent about any conflicts of interest or funding sources. In 2026, AI tools can help identify bias by flagging when your selected literature skews heavily toward one perspective or methodology, but human oversight remains essential.

Q: What’s the difference between systematic review, scoping review, and literature review?A: These three approaches to reviewing literature differ in purpose, rigor, and methodology. A systematic review aims to answer a specific, focused research question using exhaustive search strategies, explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria, critical quality appraisal of included studies, and often meta-analysis combining quantitative results—it’s the gold standard for evidence-based medicine and policy. A scoping review explores the breadth of literature on a topic to map key concepts, types of evidence, and research gaps—it casts a wider net than systematic reviews, doesn’t always appraise study quality, and aims for comprehensiveness over evaluation. A traditional literature review (also called narrative review) surveys relevant literature on a topic less systematically, may not document search strategy exhaustively, focuses on synthesis and interpretation, and is more common in dissertations and introductory article sections. Choose systematic review when you need definitive evidence on a specific question, scoping review when exploring emerging topics or mapping research landscapes, and literature review when providing context or theoretical grounding. In 2026, AI tools like ChatGPT Deep Research and Elicit can accelerate all three types, but systematic reviews still require the most rigorous human oversight.

Q: How do I create an effective search strategy for academic databases?A: Creating an effective academic search strategy involves several systematic steps. First, break your research question into key concepts using the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) for clinical questions or a similar conceptual framework for other domains. For each concept, identify synonyms, related terms, and variations—for example, if researching “elderly,” also include “older adults,” “seniors,” “aged,” etc. Use Boolean operators strategically: AND to combine different concepts (diabetes AND exercise), OR to include synonyms (elderly OR seniors OR aged), and NOT to exclude irrelevant terms (carefully, as this can eliminate relevant papers). Apply database-specific controlled vocabulary like MeSH terms in PubMed, subject headings in other databases—these standardized terms improve precision. Use truncation symbols () to capture word variations: “therap” finds therapy, therapies, therapeutic, therapist. Apply phrase searching with quotation marks for multi-word concepts: “machine learning” rather than machine AND learning. Test your search strategy on a small scale first, refine based on results, then run comprehensive searches. Document your complete search strategy including date searched, database, exact search string, and filters applied—this ensures reproducibility. In 2026, AI tools like Perplexity can help generate initial search terms, but human refinement based on preliminary results remains crucial.

Q: Should I include gray literature in my research?A: Whether to include gray literature (unpublished reports, white papers, conference proceedings, dissertations, government documents, etc.) depends on your research goals and discipline. Include gray literature when comprehensive evidence is needed for systematic reviews, to address publication bias favoring positive findings, researching recent topics where peer-reviewed publications lag, examining policy or practice questions where relevant evidence appears in reports, or conducting research in developing fields with limited published literature. Gray literature may be less appropriate when journal peer review is essential for quality assurance, conducting meta-analysis requiring standardized reporting, facing strict time or resource constraints, or when your field’s conventions exclude it. If including gray literature, search specialized databases like OpenGrey, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, government websites and organizational repositories, conference proceedings databases, and preprint servers like arXiv or medRxiv. Apply the same critical appraisal to gray literature as published work—potentially more stringently since it hasn’t been peer reviewed. Document your gray literature search strategy as thoroughly as your database searches. In 2026, AI tools like ChatGPT Deep Research automatically include some gray literature in searches, so be aware of source types in your results.

Q: How many papers should I include in my literature review?A: There’s no magic number—the appropriate number of papers depends on your research question scope, topic maturity, available literature, review type, and depth required. For highly focused systematic reviews on well-researched topics, you might include 15-30 carefully selected, high-quality papers. For broader scoping reviews mapping a research landscape, 50-100+ papers may be appropriate. For doctoral dissertation literature reviews, typically 40-80 sources demonstrate comprehensive understanding. For preliminary or rapid reviews with time constraints, 20-30 key papers may suffice. Quality matters more than quantity—better to thoroughly analyze 25 highly relevant, methodologically sound papers than superficially cover 100 papers. Your inclusion should be driven by concept saturation (no new themes emerging) rather than hitting an arbitrary number. Systematic reviews with meta-analysis might include any number from 5 to 500+ depending on the clinical question and available RCTs. In business or interdisciplinary research, expect higher numbers due to broader scope. Document your screening process: starting with 500-2000 initial search results, screening down to 50-200 abstract reviews, and finally including 20-100 in your final synthesis. In 2026, AI tools can help manage larger literature sets, but don’t inflate numbers artificially—focused, critical analysis trumps comprehensive coverage of tangential papers.

Q: What are the best tools for managing research citations and references?A: The leading citation management tools in 2026 each excel in different use cases. Zotero (free, open-source) offers browser integration for one-click citation saving, automatic metadata retrieval, PDF annotation and organization, citation style flexibility (9000+ styles), and collaboration through shared libraries—best for researchers on a budget or those valuing open-source software. Mendeley (free with paid premium) provides similar features plus stronger social networking features for following researchers and discovering papers, better mobile apps, and owned by Elsevier so integrates well with Scopus. EndNote (paid, ~$250) remains standard in many academic institutions with the most comprehensive citation styles, excellent Word integration, and traditional desktop application preferred by some researchers—best if your institution provides it or you’re in sciences. Papers (paid) focuses on Mac/iOS users with beautiful interface, smart collections for organization, and integration with Apple ecosystem. Notable (free, newer) offers modern interface with fast search and emerging AI features. For collaborative research, consider Zotero or Mendeley with shared libraries. Many researchers use multiple tools: Zotero for collecting/organizing, then exporting to EndNote for writing if required by journals. In 2026, several tools are adding AI features—semantic search within your library, automatic paper recommendations based on your collection, and smart summaries—with Zotero plugins like Zotero-GPT leading innovation in the open-source space.

Q: How do I synthesize findings across multiple research papers?A: Effective synthesis moves beyond summarizing individual papers to identify patterns, themes, and insights across the literature. Start with thematic analysis: as you read papers, note recurring concepts, methodologies, or findings; group papers addressing similar aspects of your research question; identify areas of consensus (what do most papers agree on?) and disagreement (where do findings or interpretations diverge?). Create a synthesis matrix—a table with papers as rows and key dimensions as columns (methodology, sample size, findings, limitations)—this visualizes patterns across studies. Look for chronological trends showing how understanding has evolved over time, gaps where research is lacking, and methodological patterns like whether certain methods consistently produce different findings. Develop a conceptual framework integrating findings into a coherent theoretical model. Write thematically, not paper-by-paper—organize your synthesis around themes or concepts, citing multiple papers within each theme rather than summarizing each paper separately. Critically analyze rather than just describe—explain why findings differ, evaluate strength of evidence, and identify implications. In 2026, AI tools dramatically accelerate synthesis: upload papers to Claude Projects and ask “identify common themes across these papers” or “where do these papers disagree on [topic]?” Use ChatGPT to draft thematic syntheses, then verify against source papers. The AI can spot patterns across dozens of papers that would take humans hours, but you must verify accuracy and add critical insight AI cannot provide.

Q: What is critical appraisal and how do I do it?A: Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of research quality, validity, and relevance to your research question—it separates high-quality evidence from weak or biased studies. For quantitative research, evaluate study design (RCTs provide stronger evidence than observational studies for causal claims), sample size and selection (adequate size? representative?), methodology rigor (clearly described? appropriate for research question?), statistical analysis (appropriate tests? clearly reported? effect sizes meaningful?), bias and confounding (did researchers control for alternative explanations?), and generalizability (can findings apply beyond the specific study context?). For qualitative research, assess research design fit with question, data collection rigor, analysis transparency and depth, reflexivity (do researchers acknowledge their role and biases?), and transferability of findings. Use standardized critical appraisal tools rather than ad-hoc judgment: CASP checklists (different tools for RCTs, qualitative studies, systematic reviews, etc.), GRADE for assessing evidence quality in systematic reviews, Cochrane Risk of Bias tools for clinical trials, JBI checklists covering many study types, or STROBE for observational studies. Critical appraisal should inform both which papers you include (some may be too flawed) and how much weight you give to findings in your synthesis (high-quality studies deserve more influence). Document your appraisal decisions transparently. In 2026, AI can assist by extracting key methodological details and flagging potential bias issues, but human expertise is essential for nuanced quality judgment.

Q: How can I ensure my literature review is reproducible?A: Research reproducibility has become a central concern in 2026, and literature reviews must meet the same standards as primary research. Document everything: create and save your detailed search protocol before beginning, record exact search strings for each database including dates searched, specify inclusion/exclusion criteria with examples of edge cases, maintain a log of all screening decisions and reasons for exclusions, and save citation records and full texts of included papers. Use PRISMA flow diagrams showing numbers of papers at each screening stage even for non-medical reviews—this transparency is increasingly expected across disciplines. Consider pre-registering your systematic review protocol on platforms like PROSPERO (health sciences) or OSF (open science) to document your methodology before seeing results. Make your data available: deposit your full dataset of included papers, extraction spreadsheets, and analysis files in public repositories like OSF or FigShare where appropriate and allowed. Use persistent identifiers like DOIs when citing papers. If using AI tools, document which tools, which versions, what prompts you used, and how you verified AI-generated content. Version control your work using Git/GitHub or detailed file naming showing dates and changes. The gold standard is that another researcher could follow your documented process and arrive at the same set of papers and similar conclusions. Reproducibility not only strengthens your work’s credibility but protects you if questions arise about your methodology later.

Q: What are the most common mistakes in conducting deep research?A: Researchers frequently make several preventable mistakes in literature reviews. Starting without a clear research question leads to unfocused reviews covering too much without adequate depth—solve this by refining your question before searching and using PICO or similar frameworks. Using inadequate search strategies like searching only Google Scholar or a single database, missing relevant literature—always search at least 3-4 databases and consider gray literature. Poorly documented methodology makes your research non-reproducible and raises questions about rigor—document everything from day one. Screening bias where researchers unconsciously select papers supporting their hypotheses while excluding contradictory evidence—use pre-specified inclusion/exclusion criteria and ideally have a second reviewer. Publication bias by including only published papers and missing null findings or unpublished research—actively search for gray literature and consider contacting researchers for unpublished data. Inadequate critical appraisal treating all papers equally regardless of quality—use standardized appraisal tools and weight findings accordingly. Paper-by-paper summary rather than thematic synthesis misses the point of literature reviews—synthesize around themes and concepts. Plagiarism or inadequate paraphrasing often unintentional when taking notes—always use quotation marks for direct quotes and cite generously. Time mismanagement underestimating how long thorough review takes—start early and create realistic timelines. Not using reference management software leads to citation chaos—adopt Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote from the start. In 2026, AI tools can help avoid some pitfalls (like expanding search strategies or organizing thematically), but others like publication bias and critical appraisal require conscious human effort.

Conclusion: Your Roadmap to Rigorous Deep Research Methodology

Deep research, often called systematic research or a Comprehensive Literature Review (CLR), is the fundamental process for moving beyond simple summaries to generate profound, new insights. This methodology begins by demanding precision in scope: Defining the problem, formulating a specific, answerable research question, and establishing strict criteria for source selection. The subsequent steps are centered on rigorous evidence gathering through systematic searches, critical screening, and meticulous organization of high-quality data. Ultimately, the goal is to synthesize this collected literature, moving past individual source summaries to build a cohesive, evidence-based argument that addresses the initial research question, identifies knowledge gaps, and contributes significantly to the field. Mastering this structured approach ensures your findings are credible, comprehensive, and impactful. To further deep dive into research, the Chain of Thought (CoT) process guide will also be very helpful for you to understand and apply it in your online research journey.

Frequently Asked Questions: Mastering the Deep Research Process

These are the most common questions researchers ask about conducting thorough, systematic research. Each answer provides actionable guidance to improve your research quality and efficiency.

What is deep research, and how does it differ from regular research?

Deep research is a comprehensive, systematic approach to investigating a topic that goes far beyond surface-level information gathering. While regular research might involve reading a few articles or conducting a quick Google search, deep research requires extensive exploration across multiple sources, critical evaluation of evidence, synthesis of diverse perspectives, and rigorous documentation of findings.

Key differences:

Regular Research:

- Uses 3-5 sources

- Takes hours to days

- Focuses on answering a specific question

- Relies heavily on readily available information

- Often stops at the first satisfactory answer

Deep Research:

- Uses 20-50+ sources across various types (academic papers, books, interviews, data)

- Takes weeks to months

- Explores a topic comprehensively from multiple angles

- Seeks out primary sources and original data

- Continues until achieving a thorough understanding and identifying knowledge gaps

Deep research is essential for academic work, professional analysis, investigative journalism, policy development, and any situation where accuracy and comprehensive understanding are critical.

When should I use deep research instead of quick research?

Use deep research when:

1. High-stakes decisions depend on your findings

- Business strategy development

- Investment decisions

- Policy recommendations

- Medical treatment decisions

- Legal arguments

2. You need original insights

- Academic thesis or dissertation

- Competitive analysis for unique market positioning

- Identifying genuinely novel opportunities

- Contributing new knowledge to a field

3. The topic is complex or controversial

- Multiple competing viewpoints exist

- Conflicting evidence in the existing literature

- Nuanced understanding required

- Historical context matters significantly

4. Accuracy is critical

- Publishing research that others will cite

- Professional reports influencing major decisions

- Investigative journalism exposing wrongdoing

- Expert testimony or consultation

5. You’re establishing yourself as an authority

- Building thought leadership

- Creating definitive resources

- Demonstrating expertise to clients or employers

- Academic career advancement

Use quick research for:

- Personal curiosity questions

- Time-sensitive decisions with acceptable uncertainty

- Preliminary exploration before committing to deep research

- Low-stakes situations where “good enough” suffices

- Continuous learning and staying informed

How long does deep research typically take?

Deep research timelines vary significantly based on topic complexity, available resources, and depth required:

Quick Deep Research (1-2 weeks):

- Well-documented topics

- Abundant accessible sources

- Focused, specific question

- Example: Researching best practices for remote team management

Standard Deep Research (1-3 months):

- Moderately complex topics

- Mix of readily available and harder-to-find sources

- Requires synthesis across disciplines

- Example: Analyzing the impact of AI on a specific industry

Extensive Deep Research (3-6 months):

- Complex, multifaceted topics

- Primary research required (interviews, surveys, original data collection)

- Limited existing literature

- Example: PhD dissertation chapter or comprehensive market analysis

Major Research Projects (6-12+ months):

- Novel topics with little existing research

- Requires significant original data collection

- Multiple research methods needed

- Example: Full doctoral dissertation or book-length investigation

Time breakdown by phase:

- Question formulation and planning: 5-10% of total time

- Information gathering: 40-50%

- Analysis and synthesis: 25-30%

- Documentation and writing: 15-20%

- Review and revision: 5-10%

Pro tip: Most researchers underestimate time requirements by 50-100%. Build in buffer time for:

- Unexpected complications in finding sources

- Dead ends requiring new approaches

- Waiting for interview responses or document access

- Deeper analysis than initially anticipated

Research Planning & Strategy

How do I formulate a good research question?

A strong research question is the foundation of effective deep research. Follow this framework:

The FINER Criteria:

F – Feasible: Can you actually answer it with available resources and time?

- Bad: “What causes all human behavior?” (Too broad)

- Good: “How does social media usage correlate with anxiety in teenagers aged 13-17?”

I – Interesting: Does it matter to you and your audience?

- Bad: “What is the history of staplers?” (Unless you’re in the office supply industry)

- Good: “How can workplace design improve employee productivity?”

N – Novel: Does it add something new rather than rehashing known information?

- Bad: “Is exercise healthy?” (Already well-established)

- Good: “How does high-intensity interval training affect cognitive function in adults over 60?”

E – Ethical: Can you research it without causing harm?

- Bad: “What happens if we deprive children of education?” (Unethical)

- Good: “What factors correlate with educational outcomes in under-resourced schools?”

R – Relevant: Does it address an important issue or gap in knowledge?

- Bad: “What’s my neighbor’s favorite color?” (No broader significance)

- Good: “How do color preferences influence consumer purchasing decisions?”

Question formulation process:

- Start broad: “I’m interested in artificial intelligence.”

- Add specificity: “I’m interested in how AI affects employment.”

- Narrow further: “I’m interested in how AI automation affects manufacturing jobs.”

- Make it researchable: “How has AI automation affected manufacturing employment in the Midwest U.S. from 2015-2024?”

- Refine based on initial research: “What factors determine whether manufacturing facilities adopt AI automation, and how does this adoption affect employment levels and worker roles?”

Question types:

- Descriptive: “What is happening?” (Good for exploratory research)

- Explanatory: “Why is this happening?” (Identifies causes and mechanisms)

- Predictive: “What will happen?” (Projects future trends)

- Prescriptive: “What should be done?” (Develops recommendations)

Start with descriptive questions, then move to explanatory or prescriptive as your understanding deepens.

What tools and resources do I need for deep research?

Essential tools for modern deep research:

Research Databases & Search:

Academic Sources:

- Google Scholar (Free) – Academic papers, citations

- JSTOR (Subscription, often through university) – Humanities and social sciences

- PubMed (Free) – Medical and life sciences

- IEEE Xplore (Subscription) – Engineering and technology

- ArXiv (Free) – Preprints in physics, math, computer science

General Sources:

- Google Advanced Search – Powerful filters for regular web content

- Library Genesis – Access to books and papers (legal status varies)

- Internet Archive – Historical web pages and documents

Reference Management:

- Zotero (Free) – Citation management, PDF organization, note-taking

- Mendeley (Free) – Similar to Zotero with social features

- EndNote (Paid) – Professional-grade reference management

Note-Taking & Organization:

- Notion (Free/Paid) – All-in-one workspace for notes, databases, project management

- Obsidian (Free) – Markdown-based notes with powerful linking

- Evernote (Free/Paid) – Classic note-taking with good search

- Roam Research (Paid) – Network-based note-taking

Analysis Tools:

- NVivo (Paid) – Qualitative data analysis

- MAXQDA (Paid) – Mixed methods research

- Excel/Google Sheets – Quantitative data organization and basic analysis

- SPSS/R/Python – Advanced statistical analysis

Writing & Collaboration:

- Google Docs – Real-time collaboration

- Scrivener – Long-form writing organization

- Grammarly – Writing quality checking

AI Research Assistants:

- ChatGPT/Claude – Literature synthesis, brainstorming, draft writing

- Elicit – AI research assistant for finding papers

- Consensus – AI-powered academic search

- Research Rabbit – Citation network exploration

Minimum toolkit to start:

- Google Scholar (search)

- Zotero (reference management)

- Notion or Obsidian (notes)

- Google Docs (writing)

- ChatGPT or Claude (synthesis and analysis assistance)

Total cost: $0-20/month

How do I create a research plan?

A structured research plan prevents wasted effort and ensures comprehensive coverage:

Step 1: Define Your Research Question (Week 1)

- Write your primary research question

- Identify 3-5 sub-questions

- Determine what “done” looks like (specific deliverable)

Step 2: Conduct Preliminary Research (Week 1-2)

- Spend 5-10 hours on initial exploration

- Identify key terms, concepts, and debates

- Find 5-10 highly cited or foundational sources

- Refine your question based on what you learn

Step 3: Develop Search Strategy (Week 2)

- List keywords and synonyms

- Identify relevant databases and sources

- Create boolean search strings

- Set up alerts for new publications

Step 4: Create Information Architecture (Week 2)

- Set up folder structure for sources

- Create note-taking templates

- Design a spreadsheet for tracking sources

- Establish citation system

Step 5: Set Timeline and Milestones (Week 2)

- Break research into phases

- Assign time estimates to each phase

- Set specific deadlines

- Schedule regular progress reviews

Step 6: Identify Resources and Constraints

- List available resources (databases, libraries, budget)

- Identify potential obstacles

- Develop contingency plans

- Determine if you need assistance or collaboration

Sample Research Plan Template:

RESEARCH PLAN

Project: [Title]

Research Question: [Primary question]

Timeline: [Start] to [End]

Deliverable: [Specific output]

PHASE 1: Foundation (Weeks 1-2)

□ Preliminary literature review

□ Refine research question

□ Identify key sources

□ Set up tools and systems

PHASE 2: Data Collection (Weeks 3-6)

□ Academic database searches

□ Gray literature search

□ Expert interviews (if applicable)

□ Primary data collection (if applicable)

PHASE 3: Analysis (Weeks 7-8)

□ Code and categorize findings

□ Identify patterns and themes

□ Synthesize across sources

□ Generate insights

PHASE 4: Documentation (Weeks 9-10)

□ Outline findings

□ Draft report/paper

□ Create visualizations

□ Review and revise

PHASE 5: Finalization (Week 11-12)

□ Peer review/feedback

□ Final revisions

□ Format and polish

□ Submit/publish

RESOURCES NEEDED:

– Access to [databases]

– [Software/tools]

– Expert contacts: [names]

– Budget: [amount]

SUCCESS CRITERIA:

– [Specific metrics for completeness]

– [Quality standards]

– [Deadline requirements]

Review and adjust your plan every 2 weeks. Research rarely goes exactly as planned—flexibility is essential.

Source Evaluation & Selection

How do I evaluate if a source is credible?

Source credibility is fundamental to research quality. Use the CRAAP test:

C – Currency: Is the information current?

- When was it published?

- Has it been updated?

- Is currency important for your topic? (Medical research needs recency; historical analysis may not)

- Are the links functional?

R – Relevance: Does it fit your needs?

- Does it answer your research question?

- Is it at an appropriate level (not too basic, not too advanced)?

- Have you looked at multiple sources before choosing this one?

- Would you cite this in professional work?

A – Authority: Is the source from a credible author/organization?

- Who is the author? What are their credentials?

- What organization published it?

- Is the URL a credible domain? (.edu, .gov, .org from known institutions)

- Can you verify the author’s expertise?

A – Accuracy: Is the information correct?

- Is it supported by evidence?

- Can you verify information through other sources?

- Does it cite sources properly?

- Are there obvious errors or typos suggesting poor quality control?

P – Purpose: Why was this created?

- Is the purpose to inform, persuade, entertain, or sell?

- Are biases clearly stated?

- Is advertising clearly distinguished from content?

- Are multiple perspectives presented?

Additional credibility indicators:

Strong positive signals:

- Peer-reviewed academic journals

- Citations from other credible sources

- Transparent methodology

- Conflicts of interest disclosed

- Author with relevant expertise

- Published by an established institution

- Data and sources provided

Red flags:

- Sensationalist headlines

- No author listed

- Lack of citations or sources

- Obvious bias without acknowledgment

- Poor grammar and spelling

- Extraordinary claims without extraordinary evidence

- Commercial motivation masked as information

Special considerations for different source types:

Academic papers: Check journal impact factor, number of citations, author’s h-index News articles: Verify through multiple outlets, check reporter’s track record Websites: Check “About” page, look for .edu or .gov domains, verify organization legitimacy Books: Check author credentials, publisher reputation, reviews in academic journals Social media: Verify identity, check for verification badges, cross-reference claims

When in doubt, use the “Would I stake my reputation on this?” test.

How many sources do I need for thorough research?

Source quantity depends on research scope, but here are guidelines:

Minimum by research type:

Blog post/article: 10-15 sources

- Mix of academic and practical sources

- At least 3-5 high-quality academic or expert sources

- Recent sources (within 5 years for most topics)

Undergraduate paper: 15-25 sources

- The majority should be peer-reviewed academic sources

- Include seminal works in the field

- Mix of primary and secondary sources

Master’s thesis: 50-100+ sources

- Comprehensive literature review required

- Deep engagement with existing scholarship

- Multiple perspectives represented

PhD dissertation: 100-300+ sources

- Exhaustive review of the field

- Demonstrate mastery of the domain

- Include international perspectives

Professional report: 20-50 sources

- Mix of academic research and industry reports

- Include recent data and statistics

- Cite expert opinions and case studies

Book: 100-500+ sources

- Depends on book type and scope

- Comprehensive coverage expected

- Original research often included

Quality matters more than quantity. Better to have 20 highly relevant, credible sources than 100 marginally related or questionable ones.

Signals you have enough sources:

- You start seeing the same sources cited repeatedly

- New sources aren’t adding new information

- You can identify different schools of thought

- You encounter the same arguments from multiple angles

- You can predict what a new source will say

- You’ve identified key debates and controversies

- You recognize the major contributors to the field

Signals you need more sources:

- You’re only finding sources that agree with each other

- Major questions remain unanswered

- You discover references to important works you haven’t read

- Experts you interview mention unfamiliar research

- Your topic feels incomplete or one-sided

- You can’t identify competing perspectives

Source diversity checklist:

- Academic peer-reviewed papers

- Books from credible publishers

- Government reports and data

- Industry reports and white papers, Expert interviews or consultations

- Primary sources (original documents, data), News articles from reputable outlets, International perspectives

- Historical context sources Opposing viewpoints

Research Methodology

What’s the difference between primary and secondary research?

Understanding this distinction is crucial for research planning:

Primary Research: Research you conduct yourself, gathering original data directly from sources.

Examples:

- Surveys and questionnaires

- Interviews (structured, semi-structured, or unstructured)

- Focus groups

- Experiments and trials

- Observations (participant or non-participant)

- Case studies

- Original data analysis

- Field research

- Ethnographic studies

Advantages:

- Addresses your specific question directly

- Current and relevant to your exact needs

- Control over methodology

- Original contribution to knowledge

- Can fill gaps in existing research

Disadvantages:

- Time-intensive

- Expensive

- Requires methodological expertise

- May need ethics approval

- Potential for researcher bias

- Limited sample size often

Secondary Research: Analysis of existing data and information gathered by others.

Examples:

- Literature reviews

- Analysis of published research

- Meta-analysis of multiple studies

- Review of government statistics

- Examination of historical documents

- Analysis of media coverage

- Review of company reports

Advantages:

- Faster and less expensive

- Access to large datasets

- Can cover longer time periods

- Learn from others’ methodologies

- Identify gaps requiring primary research

Disadvantages:

- May not perfectly fit your question

- Data could be outdated

- Quality depends on original research

- Possible biases in original sources

- Limited control over methodology

When to use each:

Use primary research when:

- Your question is novel or highly specific

- Existing research is outdated

- You need current, local, or proprietary data

- You’re testing a new hypothesis

- Direct experience is necessary

Use secondary research when:

- Extensive relevant research already exists

- Building on established knowledge

- Resources are limited

- Background understanding is needed before primary research

- Synthesizing existing knowledge adds value

Best practice: Most deep research combines both. Start with secondary research to understand the landscape, identify gaps, and refine your question. Then conduct primary research to address those gaps or test specific hypotheses.

How do I organize my research notes and sources?

An effective organization prevents information overload and enables efficient analysis:

Organization System Components:

1. Reference Management Use Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote to:

- Store PDFs and articles

- Generate citations automatically

- Tag sources by theme or category

- Add notes directly to sources

- Share libraries with collaborators

Setup:

- Create collections for major themes

- Tag each source with 3-5 keywords

- Rate sources by importance (1-5 stars)

- Add a one-sentence summary to each entry

2. Note-Taking Structure

The Zettelkasten Method (recommended):

- Create atomic notes (one idea per note)

- Link related notes together

- Add your own thoughts, not just summaries

- Tag for easy retrieval

- Build a knowledge network

Note template:

Title: [Concise description of idea] Source: [Citation] Date: [When you read it] Key Quote: “[Direct quote]” Summary: [Your paraphrase] My thoughts: [Your analysis] Related to: [Links to other notes] Tags: #keyword1 #keyword2

3. File Organization

Folder structure:

Research Project/ ├── 0_Planning/ │ ├── Research_Plan.md │ ├── Questions.md │ └── Timeline.md ├── 1_Sources/ │ ├── Academic_Papers/ │ ├── Books/ │ ├── Reports/ │ └── Websites/ ├── 2_Notes/ │ ├── Literature_Notes/ │ ├── Permanent_Notes/ │ └── Fleeting_Notes/ ├── 3_Analysis/ │ ├── Themes/ │ ├── Patterns/ │ └── Insights/ ├── 4_Writing/ │ ├── Outlines/ │ ├── Drafts/ │ └── Final/ └── 5_Data/ ├── Raw_Data/ ├── Processed_Data/ └── Visualizations/

4. Tracking Spreadsheet

Create a master spreadsheet with columns:

- Title

- Author(s)

- Year

- Source type

- Key themes/tags

- Relevance (1-5)

- Status (to read/reading/read/cited)

- Notes location

- Citation key

5. Synthesis Documents

Create living documents that evolve:

- Literature review matrix: Compare sources side-by-side

- Theme tracker: Collect all notes related to each theme

- Timeline: Chronological view of developments

- Concept map: Visual relationships between ideas

Best practices:

- Consistent naming: Use “YYYY-MM-DD_Author_Title” format

- Regular backup: Cloud storage + local backup

- Process immediately: Take notes while reading, not after

- Your words: Paraphrase in your own words to avoid plagiarism

- Metadata matters: Always capture full citation information

- Review weekly: Spend 30 minutes reviewing and connecting notes

- Avoid perfectionism: A good organization system used consistently beats a perfect system used inconsistently

Red flags your system isn’t working:

- Can’t find sources you know you saved

- Duplicate notes on the same topic

- Unclear which version is the most current

- Notes make no sense when you revisit them

- Can’t remember what you’ve already read

Fix these issues immediately—poor organization compounds over time.

Common Challenges

How do I avoid getting overwhelmed by too much information?

Information overload is the most common deep research challenge. Combat it with these strategies:

1. Set Clear Boundaries

Scope limitations:

- Define what’s IN scope (specific time period, geographic region, sub-topic)

- Define what’s OUT of scope (related but not central topics)

- Write these down and review before pursuing new sources

Time boundaries:

- Set research session limits (2-3 hours maximum before break)

- Establish the total research phase deadline

- Use the Pareto principle: 80% of value from 20% of sources

2. Use Progressive Depth

First pass: Skim abstracts and conclusions (30-50 sources) Second pass: Read carefully (15-25 most relevant sources) Third pass: Deep analysis (5-10 most important sources)

Don’t read everything deeply upfront.

3. Implement Filtering System

Quick assessment criteria:

- Does the title directly relate to the research question? (Yes/No)

- Is the source credible? (Yes/No)

- Is it recent or seminal? (Yes/No)

- Does abstract suggest new information? (Yes/No)

If 3+ “Yes,” add to reading list. If fewer, set aside.

4. Take Strategic Notes

Focus on:

- Ideas that challenge your assumptions

- Gaps in current knowledge

- Contradictions between sources

- Novel methodologies

- Key quotes worth citing

Avoid:

- Copying everything

- Summarizing what’s already clear

- Notes you won’t understand later

- Redundant information across sources

5. Regular Synthesis Sessions

Weekly synthesis (1-2 hours):

- Review the week’s notes

- Identify emerging themes

- Connect ideas across sources

- Update the research question if needed

- Plan next week’s focus

This prevents the accumulation of unprocessed information.

6. Use the Information Saturation Principle

Stop researching a sub-topic when:

- New sources repeat existing information

- Diminishing returns on time invested

- You can explain the topic to someone else clearly

- You’ve identified all major perspectives

Move to the next sub-topic rather than pursuing completeness on one area.

7. Create Visual Maps

Mind maps or concept maps:

- Main question in the center

- Major themes as branches

- Sources and ideas as sub-branches

- Shows structure at a glance

- Identifies underdeveloped areas

Visual representation prevents feeling lost in the details.

8. Manage Physical and Digital Space

Digital:

- Close unnecessary tabs

- Use “read later” services (Pocket, Instapaper)

- One project open at a time

- Clear desktop

Physical:

- Organized workspace

- Physical filing system

- One research project visible at a time

Cluttered space → cluttered mind.

When you’re already overwhelmed:

Emergency reset:

- Stop gathering new information (24-48 hours)

- Review what you have (quick skim)

- Create a simple outline of what you know

- Identify the biggest gaps

- Restart with a focused search for gaps only

Remember: Perfect information is impossible. Good research requires knowing when you have enough.

Content created in collaboration with Google Gemini and Claude.

Related Articles:

AI Prompt Engineering Guide for Marketing (2026)

Recent Comments